NOT many people would like to be on the receiving end of a verbal slanging from the actress and rock singer Courtney Love. She has described her fashion designer Dawn Simorangkir as a “drug-pushing prostitute”.

NOT many people would like to be on the receiving end of a verbal slanging from the actress and rock singer Courtney Love. She has described her fashion designer Dawn Simorangkir as a “drug-pushing prostitute”.

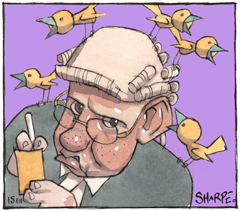

Usually, when people engage in slanging off, everyone cools down after a while and life goes on. But these days individuals can do more than have a rant at the shop door, or a scream across an office. They have greater publishing power at their fingertips. They can put their rant on Twitter or Facebook, and recipients can resend it via their Tweets and Facebook to others. This is what Love did. Simorangkir did not like it, particularly as Love has 40,000 followers on Twitter.

Simorangkir is suing, and the case begins in Los Angeles next week. US legal developments usually do not have a lot of bearing on the Australian scene, but technological and societal changes do. Sure enough, many Australians use Twitter and Facebook and sometimes they post things which others do not like.

There is an Australian Twitter case, or rather a “matter” because it has not been before a court yet, and may never get there. The editor-in-chief of The Australian, Chris Mitchell, was quoted in his own newspaper as saying that he intended to sue University of Canberra media academic Julie Posetti over a post on her Twitter account.

The Tweet was reportage of proceedings of an academic conference, not in the same frame as the Courtney Love outburst.

The big question is should publication on Twitter or Facebook be any different from older forms of publication when it comes to defamation?

Mitchell was quoted as saying he thought there should be none. That is certainly true of the legal position: it does not matter how you publish as long as you publish to a third party – Morse code, flags, Twitter, newsprint or a thumbnail dipped in tar.

But there are some practical differences, which may have legal ramifications, some in favour of plaintiffs others in favour of defendants.

First, most mainstream publishers have a system of editing and vetting. Done well this should reduce exposure to defamation actions. Done badly, it makes the defamation worse because plaintiffs say: “Here is a big, trustworthy, diligent publisher with high credibility. If I get defamed in that publication people will believe it. It is more damaging.” Whereas people are less likely to take a large amount of notice about throwaway lines by individuals on Twitter.

Secondly, mainstream media has a deep pocket so is more likely to be sued. If you sue an individual, on the other hand, there will only be a few entrails left over after legal costs have been extracted from the carcass. It is not worth a plaintiff’s while unless he or she is backed by an organisation willing to spend money to prove a “principle”.

Thirdly, Tweets are restricted to 140 characters. That does not leave much room for a defence of fair comment on the facts truly stated.

Fourthly, Tweeters might argue that their Tweets do not go to many people compared to the large circulations of large newspapers and broadcasters, so are less damaging. But conversely, plaintiffs can argue that Tweets go to specialist audiences, usually to the very people in whose eyes they hold their reputation most dear and so are more damaging.

For example, the people who follow Love on Twitter – poor deluded twits – would be the very people in whose eyes Simorangkir would hold her reputation as a designer most dear. Similarly, Mitchell might argue the same about a niche of journalists who follow Posetti on Twitter.

Fifthly, a lot of Tweets are about things observed in the public domain. The 2006 law gives more leeway for the fair and accurate publication of defamatory imputations made at public or corporate meetings. So you could publish that at a company meeting a shareholder accused a director of being liar (if that’s what happened), without having to prove the truth of the accusation that the director is a liar. But it is difficult to cram a fair and accurate report into 140 characters.

Lastly, it is often the case that in the social media publishers are merely slanging off. Defamation law sets the test as “lowering the estimation of the plaintiff in the eyes of right-thinking people”. Now right-thinking people do not take much notice of general slurs, such as Smith is a moronic, mysoginist, twerp. But as you get more specific you drift into more trouble: “prostitute” and “drug-pushing”, for example.

As so often with the law, the ink is hardly dry, in legal timescales, on a reform when it becomes outdated.

For a quarter of a century lawyers, politicians, the media and other publishers, and academics argued about how to bring Australia’s eight 19th century defamation regimes into a single, national law that gave at least some concession to the environment of a 20th century democracy. The result was the uniform 2006 defamation law.

It already hopelessly outdated. Those who mulled over the law for that quarter century did not consider self-publication to the world via the world wide web.

The big-ticket item in this is privacy.

Significantly, the 2006 law dropped the requirement in half the Australian states that a publication be in the public interest before you could successfully defend a defamation action. It meant that you could not dredge anything any old muck, however true or trivial, from the past and republish it with the defence that it is true. In most states you had to also prove it to be in the public interest.

I have always thought that requirement to be fair enough. But no, the media forces won their pyrrhic victory and truth alone is a now a defence to defamatory publication. As long as it is true any muck about anyone can be dredged from the distant past and be published.

This is a pyrrhic victory because with the advent of the social media, many are wary about the ease with which personal details are being bandied about in the public domain. They are rightly calling for greater rights to privacy.

So mainstream media may have got away with the removal of the requirement to prove public interest in defamation cases for now, but the upshot will be a greater demand for a full-scale privacy right which will enable people to sue for high damages upon its breach.

In any event, it is now apparent that the advert of the social media and the ease with which a single individual can publish material about other people without organisational vetting will demand a revisit of the 2006 defamation law.

CRISPIN HULL

This article was first published in The Canberra Times on 15 January 2011.

Oh, also we have “defamation per se” in many states. Defamation per se are things that are considered to harm one’s reputation, whether or not you can show actual monetary loss or damages from the statement. The statements about the dress designed fit defamation per se in several ways. Accusing someone of a serious crime (drug pushing and prostitution) is defamation per se. And saying someone is unfit for their work is also defamation per se.

What this means is that the dress designer will not need to show that she lost clients or lost business because of the statements. It will be up to a jury to place a monetary figure on this. This one is difficult. It is my impression that most people view Courtney Love as a very troubled person, and therefore, who would give credence to anything she says? On the other hand, the situation surely caused the dress designer a lot of humiliation and stress. The jury will consider these factors when setting the amount of the judgement award. Most likely, the case will settle out of court. Probably the best thing would be for Ms. Love to offer a big public apology and a good amount of money.

Very interesting article! I am a lawyer in the U.S. and I have worked on defamation issues. In the U.S., there is no “public interest” requirement as such. However, it can be invasion of privacy, which is a different tort from defamation, if you publish a true statement about someone, but that is not apt for publication or newsworthy. For example, If a person is accused of a crime, you cannot publish details of their relative’s lives. And if a person is accused of a crime and goes through whatever legal process, you cannot then 10 years later dredge up a story about them. And you cannot just publish information on private people.

Here, we divide up between private figures (most people), public figures for a certain purpose, and public figures, and elected or government officials. We give great leeway to publishing about elected or government officials, but with regard to their work as a government official.