IN THE In the season of conspicuous consumption, consumption taxes are in the news again this week.

The British Government confirmed it would increase its equivalent to the GST (the VAT) to 20 per cent, up from 17.5 per cent.

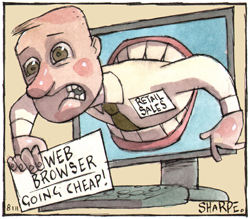

And in Australia a coalition of retailers are crying foul over Australian consumers buying stuff GST-free overseas.

These are the same retailers, by the way, who along with their suppliers, have spent the past couple of decades scavenging around the world to find the cheapest, dirtiest labour and tax regimes possible in order to maximise their profits and savings. Mercy forbid that workers and consumers should try to do the same thing.

Evading the 10 per cent GST is not driving Australian consumers to overseas retailers. Ten per cent is simply not enough to divert an Australian consumer away from the security of physical or even on-line purchases from an Australian retailer with the attendant consumer-protection laws and retail-reputation practices that remove most of the risk from dud purchases.

Rather, Australian consumers are going online because of vast differences in prices for the same product. It is cheaper to buy Japanese camera gear online from the US than either online or in-store in Australia. And we are closer to Japan.

So it is high profit margins and inefficiency not the GST that causes the electronic flight of consumers overseas.

Sure, that inefficiency might not all be the retailers’ fault. Government regulation, planning restrictions, industrial-relations regimes and the like no doubt contribute.

But if Britain, 40kms from contintental Europe, feels secure in upping its GST we can be fairly confident that tax is not the primary reason for consumers going electronically off-shore.

Nor is the high Australian dollar – a reason much cited by the retail giants. The level of the Australian dollar should surely be neutral in this. The high Australian dollar gives the same boost to purchasing power online as it does to the purchasing power of imported goods in an Australian retail store.

With one massive provisio – that Australian retailers are passing on the benefits of the high Australian dollar to consumers in the form of lower prices for imported goods and not stuffing it into their own designer-jeans pockets.

There are couple of lessons in this for government – in this year of “decision and delivery”.

The most important is that in a hi-tech economy individuals and organisations respond fairly quickly to changing conditions. That is the nature of a competitive economy. It means that governments must equally respond reasonably quickly to changing conditions, especially on the tax front.

True, Australian governments have been pretty good at patching up emerging one-by-one defects in the tax system. Usually only one or two horses bolt before the loophole in the stable door is closed.

But governments have been much slower to change large sections of the tax regime to suit changing conditions. Most recently, the response by the present government to the Henry Tax Review was woeful.

Out of dozens of sensible suggestions it picked just one of the significant suggestions – the mining tax – and completely messed up the process to implement it.

But worse than messing up the mining tax, it in effect knocked on the head the other suggestions, at least in the medium term.

The two most important of those, perhaps, were to wind back John Howard’s irresponsible boost to middle class welfare under which cheques were posted out to income-earning families – “Gosh, thank you, Mr Howard” – but the amounts were later taken back in income tax.

Good for Howard’s election chances, but bad government.

Treasury head Ken Henry saw the folly in this and urged reform. But the Rudd-Gillard Governments put the recommendations aside. Along with other sensible suggestions like road-use charges and removing inefficient taxes (payroll, stamp duty etc).

Even before the review began, critical areas were put beyond its purview: the GST, the family home and superannuation.

But these, and capital gains tax, cried out most for change.

The GST has been a worthwhile tax. It should be higher and have fewer exemptions. For a start, rent should be subject to GST. Have no fear, tenants would not be paying, landlords would, especially if in the transition landlords were prohibited from increasing rents beyond existing lease provisions.

At present, the Federal Government gets virtually nothing out of the rental market. In some years negative gearing has resulted in the Tax Office giving more in deductions than it has taken in tax. Abolishing negative gearing has been tried and failed, but imposing the GST on rents would work.

The GST is more difficult to avoid – if the rich want to spend they have to pay tax.

A higher and wider GST would leave room for lower income taxes. In particular, it would allow a more much more generous transition from welfare to work. At present, many people on welfare, particularly low-skilled people with children, have little incentive to go to work. After they pay childcare and other costs for going to work they are little better off financially despite the loss of time and effort to work.

The system should be changed so that tax is not a disincentive for people to work.

And income tax should be indexed to stop the absurd merry-go-round of bracket creep followed by so-called tax “cuts”.

The taxes on superannuation are far too generous to people over 60 with large accounts. We are taxing on the way in and on earnings in the fund and not on withdrawals. It should be the other way around.

Capital-gains tax needs an overall.

Sure, tax is difficult for politicians. Losers scream very loudly. But Australia’s tax system is messy, complicated and inefficient. Yes, we can bumble along with the present system, but overall it is not working well – that’s why we had the Henry review in the first place.

In this year of decision and delivery, the Government should revisit the Henry review. It should remove the no-go areas of the original review and seek other options.

The tax debacle was not limited to the mining tax. The effective ruling out of all the other options was the worst policy failure.

A well-led government should be able to explain the need for wide tax reform. It should be able to throw the proposals to a wide debate without scaring the horses.

Further, comprehensive reform is less subject to silly Opposition mantras like “a great big new tax”, the more so if the Government says that nothing is ruled out and that nothing will be ruled in without wide debate and consultation.

CRISPIN HULL

This article was first published in The Canberra Times on 8 January 2011.