Far too many economists, commentators (me included), policy advisers, politicians of all stripes, and voters were taken in by the intellectual appeal of economic rationalism in the 1980s and 1990s.

We failed to see how the selfish, the charlatans, and the opportunists in the corporate world would grasp the whole Thatcher-Reagan (and in Australia Hawke, Keating and Hewson) philosophy and turn it into a massive enterprise to grab public money and stuff it into their private pockets.

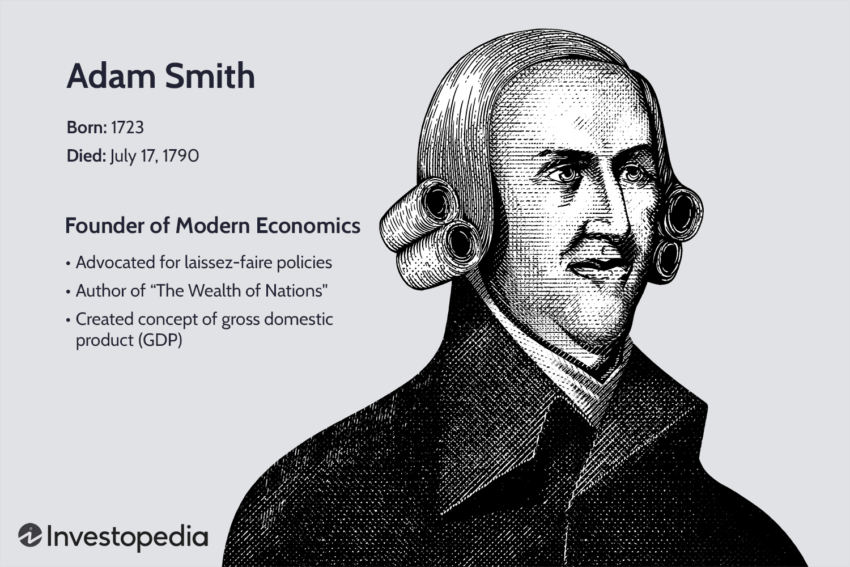

It is not as if we were not warned. As far back as 1776 Adam Smith wrote in The Wealth of Nations, “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the publick, or in some contrivance to raise prices.”

President Dwight Eisenhower warned against the military-industrial complex in 1961.

Some rare voices were against the whole privatisation-deregulation enterprise from the beginning. A stand-out has been John Quiggin whose book After Neo-Liberalism was published by ANU Press last week.

He challenges anyone to cite a case of privatisation that was of benefit to the public at large.

He is right. Remember the kerosene baths in the privatised aged-care homes during the Howard Government. Remember how Labor sold the Commonwealth Bank between 1991 and 1995 for a catastrophically underprice of between $5.40 and $10.45 a share.

Once an ethical leader in Australian banking it descended in venal criminality, as found by the Banking Royal Commission – charging dead clients and the like.

Rod Sims, the former head of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, was once an advocate of privatisation, but he soon began asking what is the point of demolishing an inefficient, over-charging, public monopoly with a greedy, selfish, over-pricing private monopoly?

The fundamental point is that corporations simply cannot be trusted to do the right thing. To the contrary, unless constrained by regulation, you can almost guarantee they will do the wrong thing to the detriment of the public good and to the detriment of competition, productivity, and economic health in general.

Last week, the Assistant Minister for Competition, Charities and Treasury, Andrew Leigh, outlined the half-century of woeful history of Australia’s regulation of corporate mergers.

He said it is hard to point to any sector of the Australian economy that is not dominated by just a handful of players – as shoppers at Coleworths are reminded daily.

At least he and the Government more broadly are doing something about it. The plan is to improve the merger-approval process.

“Mergers that create, strengthen or entrench substantial market power will be identified and stopped while those consistent with our national economic interest will be fast tracked,” Leigh said. “There will be a public register of all mergers and acquisitions notified to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission to promote transparency and accountability.”

Notification will be compulsory for proposed mergers above a monetary or market-concentration threshold. The scheme will begin on 1 January next year.

It is a good move that will prevent increased monopolisation in the future. But what of all the horses that have already bolted: banks, supermarkets, insurance, airlines, to name a few?

Moreover, regulating mergers through the ACCC is only part of the story of corporate behaviour. A perhaps more significant element is the effectiveness of that regulation. Last month a Senate inquiry – chaired by Coalition Senator Andrew Bragg – issued a scathing report about the Australian Securities and Investment Commission’s lack of performance.

Bragg said there were too few criminal convictions for breaches of corporate law.

“Australia is a haven for white-collar criminals,” he said.

And this is from a Coalition senator – the side which goes easy on business.

The inquiry recommended that: “The Australian Government should recognise that the Australian Securities and Investment Commission has comprehensively failed to fulfil its regulatory remit.”

It called for more comprehensive investigation of allegations of corporate misconduct.

It is no good having a watchdog, even one with considerable legislative teeth, if it will not bite occasionally.

Another element of corporate culture in Australia that incessantly fails the broad public is the way corporates insinuate themselves into the legislative process to water down anything which might erode profits: food standards; chemicals; water quality; advertising rules; scam control, and so on.

Corporates have the ear of political Australia to, in the words of Adam Smith, conspire against the public. And their donations to political parties are part of the conspiracy.

For example, I hope I am wrong, but I bet (and I use the word on purpose) that the Government’s response to the parliamentary committee’s recommendation on a phased-in ban on online gambling advertising will be a wishy-washy cop-out.

The fact that the Government has had the report for more than a year is ominous and disgraceful. In that time the gaming industry has been privately chewing the Government’s ear and bribing political parties with big donations – as evidenced by the $50 million of disclosed donations from the industry in the decade to 2019-20. All the while lives are ruined. The Coalition would be no better.

It is the same with food labelling, taxes on sugar (which have been hugely successful in Europe), and any number of worthwhile policies to improve public well-being but would impinge on corporate profits.

The only cure is to ban all corporate donations to political parties and candidates, including those from unions, and to have an easy-to-access real-time reporting of politicians’ meetings.

Corporate donations are made to influence legislative outcomes in favour of the corporations. It is not only in their DNA, but it is enshrined in corporate law. Corporations must act in the interests of shareholders (get a monetary result), not donate as some charitable good citizen, as they argue.

If Australians are to get the undoubted benefits of the corporate structure – which pools resources, separates management from ownership, and limits risk – government needs to put them on a tighter rein.

Crispin Hull

This article first appeared in The Canberra Times and other Australian media on 6 August 2024.

John Quiggin was a contributor to the 2018 compilation “Wrong Way. How privatisation & Economic Reform Backfired” edited by Damien Cahill & Phillip Toner. Like all attempts to challenge the academic and political hegemony of neoliberalist economics it was quickly remaindered.

The current Federal Government is just as wedded to the neoliberalists as all the others of the last 75 years when they start spouting nonsense like “mergers and takeovers that are good for competition”. By definition, removing a player cannot do anything but reduce competition regardless of claims (usually spurious or never realised) of better outcomes for consumers.