The true prescience of one of Australia’s greatest public-policy successes was revealed in the sixth Inter-Generational Report published last week.

Thirty-one years ago, despite vehement opposition from the Liberal and National Parties and deep scepticism from business, Labor’s Superannuation Guarantee legislation passed the Parliament.

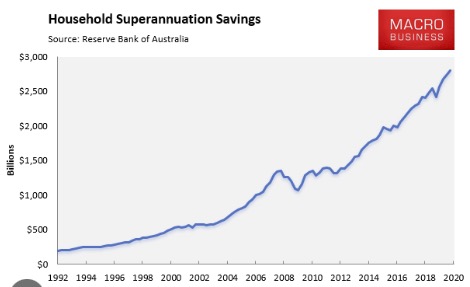

It provided that 3 per cent, rising to 12 per cent over time, of employees’ incomes would be compulsorily put into superannuation. The resulting funds now total $3.5 trillion.

Without that, as the Inter-Generational report shows, Australia’s public finances would be in a parlous state indeed.

The Inter-Generational report, of course, is supposed to highlight grim realities for the future unless we make policy changes to avert them. But too often they are used by politicians and lobbyists to push short-term agendas. Indeed, the very first one brought down by then Treasurer Peter Costello was used to push well-trodden ideological paths – cut government spending, privatise, give tax cuts to the top-end etc.

Prime Minister Paul Keating did not need an Inter-Generational Report to tell the Government the bleeding obvious – unless something was done the age pension would be an unsustainable drain on the public purse. And fairness demanded it.

Keating did something. It was long-term and would not bear any electoral fruit over the three-year political cycle, and nor was that sought.

The short-termist opponents attacked it as stealing or tying up workers’ money and imposing “unnecessary burdens” on business.

Over the next 31 years, the Coalition in the Parliament and in the media opposed or delayed every single increase in the contribution rate and supported every madcap scheme to allow people to get early access to their funds for things like housing and living expenses during Covid.

They hated the idea that ordinary workers could get access to a decent retirement income and hated even more that workers’ representatives would have a major say in the administration of the funds.

Before the scheme, superannuation with its tax perks was the preserve of the managerial and professional classes and the money was managed by the Coalition’s mates in the finance industry.

Another reason the Coalition was opposed to compulsory superannuation was that they would rather the workers blow the money today to the great profit of the retail industry.

But compulsion was the key to the scheme’s success. Experience and human nature tell us that the great majority of people do not save for a rainy day unless they are forced to.

Indeed, the early-release scheme during Covid revealed that nearly all the money people were allowed to take out prematurely was taken out and flushed down the retail toilet with nothing to show for it.

Without the superannuation scheme, it’s a fair bet that nearly all of the $3.5 trillion in funds would have ended up in landfill via the retail and consumer-junk industries.

One of the difficulties with well-thought-out schemes to be implemented over the long-term is that they are open to sabotage by politicians seeking short-term advantage.

The underlying success of the scheme, however, means that now, mercifully, it cannot be significantly unwound, but few of its earlier opponents would now admit they were wrong.

The scheme pays out about $90 billion a year, compared to the cost of the aged pension of about $70 billion. Without that $90 billion being paid mainly to people over 65, the demands on the pension would have been vastly higher and inequality much worse.

Further, contributions keep rolling in – $130 billion a year, $90 billion of which is from compulsory contributions and $40 billion voluntary.

In short, the scheme is more than sustaining itself. That fact exposes one of the great misconceptions regurgitated by the Inter-Generational Report. The misconception is that the ageing population will cripple the Australian economy. The so-called dependency ratio with fewer workers supporting ever-more dependants is cited as a need for action.

That action is so-often an agenda only tenuously linked to the so-called problem – such as higher immigration (which only makes the problem worse) or deeper cuts to government spending (which only drives resources to the much-less-efficient private sector that has failed us so miserably in health and education over the past three decades).

In 1992 Australia was capable of delivering excellent long-term public policy whose fruits are now manifest.

These days short-termism and negative campaigning make that extremely difficult. Even unwinding some of the sabotage to superannuation, education, and Medicare seem beyond the political system.

But the Intergenerational Report tells us what are the fair and economically sensible things to do. The tax burden is falling increasingly and unfairly on the young and their labour, leaving the old and their capital accumulation relatively unscathed.

High immigration has been causing a housing crisis over the past two decades.

Government might well say removing superannuation tax breaks is politically difficult, but the value of the tax breaks could be calculated and posted against each superannuation account each year. If a superannuant died and therefore did not use those tax breaks for retirement, the estate should have to repay the lot. It would drive people into taking annuities and end the nonsense of superannuation being used for estate planning and inheritance.

To the extent that the ageing population poses a problem it is in health care, which is one for all of us. We need to return to the ideal of Medicare: free, universal, timely, quality health services. It would mean a substantially higher Medicare levy and the removal of inefficient subsidies of and incentives for private health insurance.

The result would have to be an improvement on what we have now: massive, prohibitive gap fees with highly paid private specialists, on one hand, and a stretched underpaid primary-health-care system in which GPs struggle to give the time and attention needed to each patient.

We can do better. But to end on a bright spot in the public policy sphere, last week, the Federal Government like its predecessors of both complexions for decades past yet again made first-rate appointments to the High Court, elevating Justice Stephen Gageler to the Chief Justiceship and appointing Justice Robert Beech-Jones of the NSW Supreme Court to the vacancy caused by that appointment.

Both have first-rate legal minds, are well-respected in the profession, and are without a skerrick of political colouring. We are not following the US on this score.

Crispin Hull

This article first appeared in The Canberra Times and other Australian media on 29 August 2023.

Well said: the superannuation guarantee is a God-send to all of us retirees

I’m one of those fortunate retired boomers living on superannuation without paying any tax. Being over sixty, I make use of health services quite a bit. However, if the Medicare levy rose, I wouldn’t be paying it. I would support a Medicare levy being imposed on superannuants like me, on a progressive scale with bigger balances paying more. It would be difficult to sell politically but the “user pays” rationale would be easy to understand. If the Medicare Superannuants Levy rates were not excessive and health services improved over time, it would become just another part of the accepted tax landscape.

It is suddenly topical to explain my pseudonym. It translates as “Journey to the End of the Night”, a book by Louis-Ferdinand Celine of WWI. My pseudonym is directly relevant to my above comment on Australia’s directions since those early years working on the Superannuation Guarantee.

Through circumstance I became a cog in the Superannuation Guarantee wheel from prior to its inception. The aging Boomer generation was clear. The differing choices being made internationally were clear. The stalling by the Howard government was clear in 1996.

As sure as night follows day, the Aged Care crisis would be next. I still cannot believe the avoidance displayed from Howard onward by governments and Australians. There are clear policy fundamentals including private vs public services and funding models. We are still hiding from the realities.

Energy transition is another example of delays over 25 years. Tax reform has ceased since Howard’s GST. Ken Henry’s review is yellowing but remains relevant. It was Ken Henry as Head of Treasury who recommended the GST to Keating. You are correct in stating Medicare (and health services more broadly) needs to be modernised.

No leadership, no vision, no passion, and no political courage. I often wonder if many politicians at any level of government or party affiliations have the necessary skills to manage change.