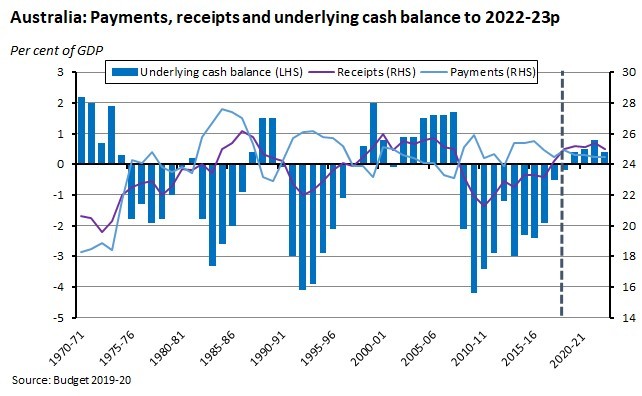

The Federal Government has posted the first actual surplus for 15 years – as distinct from a projected surplus with celebratory coffee mugs just before covid struck.

The essential lesson is not to get stuck on the mantra of “surplus good, deficit bad” and that that is the be-all and end-all of budgetary (or fiscal) policy. Governments are not like households. They do not have to keep spending within the bounds of income or go bankrupt.

And besides, as every mortgage holder knows, some debt is a good because it generates wealth in the long term.

The Government should not be congratulated on delivering a surplus (of $19 billion). Rather it should be congratulated on doing fairly well the other important elements of budgetary policy: tweaking according to whether the economy is inflationary, on one hand, or sliding into recession on the other; redistributing wealth in measured ways; promoting good economic activity and discouraging bad activity by applying taxes or tax breaks; and delivering services that people might otherwise not be able to afford.

A surplus right now is good, not because surpluses are good per se, but because the economy is in an inflationary mode which needs braking. It is better that the sledge-hammer of high interest rates does not do that alone.

Similarly, when then Treasurer Josh Frydenberg’s black “surplus” coffee mugs turned red with embarrassment after covid struck he should not have been condemned for running a deficit because deficits are bad per se. Rather, he should have been applauded for tipping money into households when it was needed.

If there had been no covid and Frydenberg’s surplus had eventuated, there still would have been good grounds for saying his fiscal policy was deeply flawed. Taking the wrecking ball the government service and vast hand-outs to mates and marginal seats for projects of dubious economic merit are no way to run fiscal policy. It was the equivalent of a household borrowing to finance holidays rather than a house.

From the 1990s, the Coalition successfully convinced much of the broader community that its obsession with surpluses was warranted. However, that obsession disguised a more passionate, but flawed, agenda: that of reducing government spending and thereby lowering taxes, especially at the higher end, at the expense of government services. That has increased inequality.

Moreover, the attacks on public services and the public service on grounds that the private sector delivers things more efficiently has now been revealed as flawed and, in many cases, corrupt.

Labor’s surplus was not built on that agenda. Rather it was a combination of high commodity prices (and therefore higher revenue) because of the Ukraine war; some fairly diligent axing of spending on consultants (especially the big four accounting/consulting firms); some axing of economically dubious and politically motivated projects; and perhaps most importantly higher income-tax revenue, particularly from the lower end and middle. That last cause is worrying.

Last week’s Parliamentary Budget report shows that the average income-tax take is 25.5 per cent, the highest this century.

Income tax will represent 50 per cent of government revenue by early next decade, unless something is done. The portion of tax on capital and company tax will fall.

But what is to be done? The legislated Stage Three tax cuts are skewed in favour of people on high incomes. They should be re-worked and the planned elimination of a middle tax bracket removed. It is unfair that someone on $40,000 will be paying the same marginal rate as someone on $199,000.

Again, intergenerational unfairness crops up. So does tax efficiency. To deal with both, the Government should introduce an automatic, say, $3000 deduction for work expenses, in effect a tax cut. It would wipe out the need for millions of Australian wage and salary earners to do tax returns and free up ATO resources for better pickings.

The ATO’s data-matching systems are very thorough. They can pick up the routine deductions and income: interest payments from banks, share dividends, and health insurance. And could be tweaked to pick up charitable donations.

Those few wage and salary earners who have higher than $3000 in work expenses could do a return backed with their receipts.

It would require a rebalancing of the tax system, with lower income taxes and higher taxes on capital and consumption. Less of the burden should fall on working young people and more on older people who get their income from capital built up in part by generous tax concessions on property, shares and superannuation.

The trouble is that increasing the tax take on incomes is easy for governments. They just have to do nothing and let inflation move more people into higher tax brackets or into the first tax bracket of 19 per cent which cuts in at $18,200.

But tackling superannuation, property, and shares requires legislation and facing well-heeled campaigns against it, as Labor found out in 2019. Tackling the unfair Stage Three tax cuts which were legislated before covid, will face similar opposition.

But that was 2019 this is 2023. The big lesson from the 2022 election and the Ashton by-election surely is that younger and female voters are responding to politicians who want greater fairness, transparency and security.

It should give the Government some confidence to move the tax base and weed out all the rorts and special treatments for the richly undeserving, and turn its attention to public health and public education – treating them as investments, not some threat to the precious surplus.

In a society like ours where by and large we do not allow people to die in a ditch from ill-health or lack of educational opportunity, ultimately the Government picks up the tab. It makes sense, therefore, that we improve primary health case and public education to avoid later costs.

Crispin Hull

This article first appeared in The Canberra Times and other Australian media on 4 July 2023.

Lifting up tent-flaps, Chalmers offers budget-surplus-on-toast, with lower-inflation coffee. He’s mostly a Treasury (or Costello) animatronic – feed the rich and flog the environment.

Spot on again Crispin