Who was at the top of the university league tables for cheating – the business school.

As the University of Sydney and University of NSW wring their hands and bewail a massive documented doubling of cheating in the past couple of years we should not be surprised.

The universities joined the neo-liberal, Thatcher-Reagan revolution of contracting out, privatisation, trickle-down economics, cost-cutting, and massive pay for Vice-Chancellors while putting tutors and junior lecturers on short-term contracts.

Why are they so surprised that business students did not see the advantage of doing the same thing? Contracting out your MBA assignment is morally equivalent to contracting out your public responsibility to provide education to a verifiable standard.

Usually I think that “good-old-days” arguments are as about as valid as comparisons with the Nazis. But with university education, the “good-old-days” argument has some validity.

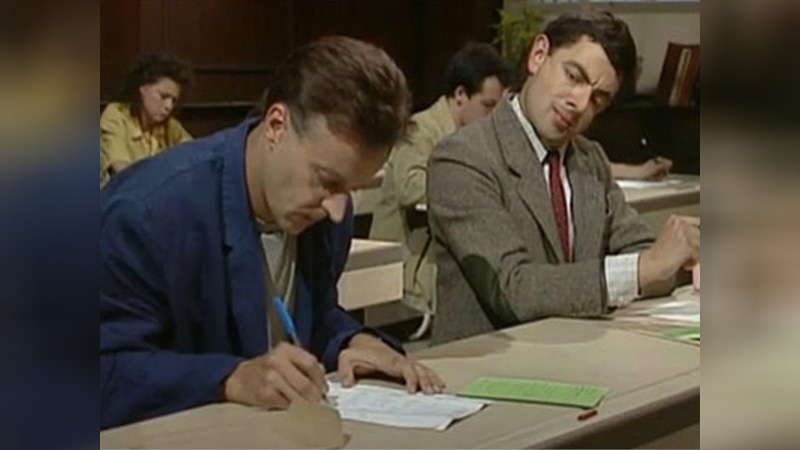

There is no better example than “Mr Bean and the Exam”. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9f2CSNyd53o )

Mr Bean, in pre-internet days, finds himself in a closed-book, three-hour exam. He has prepared for trigonometry but the exam paper is totally calculus. His in-vain attempts to copy from his neighbour under the watchful eye of an invigilator show the impossibility of cheating in such an environment.

Closed-book three-hour exams were phased out in the 1970s. They were “too stressful” for students. Diddums. Life itself is mostly a series of continually stressful, time-constrained activities. What better preparation that the three-hour exam?

But the closed-book exam gave way to the open-book exam. After all, in life you could look things up, the argument ran. But surely you need a starting base of in-brain knowledge.

Then came the no-time-limit exam. Hardly preparation for life where charge-out rates in most professions are timed by the minute.

Finally, exams were totally replaced by assignments.

That worked reasonably well for a while, but for other concurrent developments: the rise of the internet; the scramble to attract more students especially international ones; recorded lectures; larger class sizes; and less student-teacher contact.

You see, student-teacher contact is expensive. As universities morphed from educational institutions to businesses, they engaged in the sort of cost-cutting that businesses did. The results were inevitable.

Today’s students can not only go to Google, but also to people who write whole assignments for money. Indeed, whole business enterprises are set up to do just that and only that.

Results from freedom of information requests by The Sydney Morning Herald published at the weekend showed that the University of Sydney had 445 contract cheating allegations last year, about double 2019 figures, and an increase from 86 in 2018.

The University of NSW had 335 contract cheating cases last year, a 162 per cent rise compared to 2020.

Mr Bean could not have got someone else to do his exam for him.

It is quite likely that the proven contract cheating cases are like proven speeding offences – a small fraction of the total misbehaviour.

And as with speeding, technology can help expose it. But the copper on the beat is probably more effective. In the case of universities, it means more teacher-student contact. Tutors with electronic folders full of assignments submitted by students they have hardly met, let alone know, have little hope of weeding out all the fraud.

I taught journalism and law part time at the University of Canberra and the ANU for 17 years.

The ANU’s Graduate Diploma in Legal Practice program (sadly discontinued) put students into “firms” of four, to mirror real life. It had an almost foolproof way of ensuring that a student did not bludge on the other students in his or her firm. In each segment of the course each student had to do a one-on-one interview with the tutor with the tutor pretending to be the client.

The material was not rocket science. Any student (and they were all law graduates) who did the work would get through. But if they did not do the work, they would have to have another more satisfactory go or fail the course.

Classes at the University of Canberra were relatively small and could be converted to hybrid lecture-tutorials which encouraged in-person attendance. Teachers got to know their students so that the sudden production of a brilliant assignment from a student whose in-class contributions were at best lack-lustre would warrant suspicion.

But more importantly, the personal interaction would discourage out-sourcing or plagiarism in the first place.

Interestingly, law students were second bottom of the offender list. Maybe law students have a better appreciation of the rules. And who were the least likely to contract out? Music students. Maybe music schools have too much teacher-student interaction to allow someone to wheel in Ashkensazy to do their piano practical exam.

The real question, though, is who is doing the cheating here? Yes, students who contract out. Yes, the companies that take money for doing the corrupt service. But also, the universities and the governments that fund them.

We need an education model, not a business model. The business model stresses: high pay for the CEO and few others; as low pay and as poor conditions as you can get away with for other staff; contracting out; and cost cutting, especially on customer service.

The model is not even good for business. You can ruin an airline just as easily as a university.

Universities are also bedogged by another trend. They strive for a top-100 position internationally. But those league tables are determined by research results, not undergraduate teaching. So, resources are diverted accordingly. And maintenance of educational standards (to maintain the speeding analogy) goes under the radar.

This article first appeared in The Canberra Times and other Australian media on 8 Nov 2022.

When I tutored economics and math at a university in NYC, I had a private student who attended Columbia Uni. He was lazy and hardly did his homework. When final exam time came, he offered me lots of $$ to go sit the exam for him at Columbia Uni. I could have used the $$, but refused as I do have a strong sense of ethics and morals. I’m sure this kind of thing happened more than we knew.

A few years later I started MBA studies. I dropped them after 3 months as I couldn’t stomach the profit at all cost philosophy. This was the late 1970s, beginning of Reagonomics, which have led to the current results of absolute faith in the market. At least there is a bit of awareness now that trickle-down does not work. But the sense of ethics has been lost.

Virtuously, the Labor Government claims that it prefers “permanent” over “temporary” migration. On its own, their international-student deluge makes a nonsense of that. Before you even get to the temporary “skilled” migrants, on their $53,900 income threshold.

There’s this absurd pretence, they’ll keep on running the second-hugest (Canada first) immigration racket in the OECD, and somehow avoid the systemic corruption that goes with it. The Immigration Minister himself is an immigration lawyer, and Big Australia shill.

The Home Affairs Minister feeds the SMH chooks, about that bad old Peter Dutton’s visa rorts. Just you wait for the cheating rorts of the next decade. Not a single Vice Chancellor cares.

I went to ANU in the 1990s and can assure you that 3 hour closed book exams were very much a feature of my time there (and my subsequent nightmares!). Not sure where you got the idea they were phased out in the 1970s.

Sadly, all true. But even the exam-based model was flawed. When getting the piece of paper can determine lifetime earnings, the pressures all around are huge. An academic usually taught, set the exam, then marked it. What could possibly be wrong with this model? Lack of independence, perhaps.

Most academics had integrity, but there was no mechanism to prevent someone passing a favoured student, regardless of merit. This is still the case, and the pressure can be enormous. On two occasions, I had the decision taken from me because I found students to perform inadequately for them to be let lose in the workplace.

The final school qualification is taught, exams set, then marked by independent parties. The students identity is hidden. This is a process with integrity. What a pity universities have drifted so far from it.