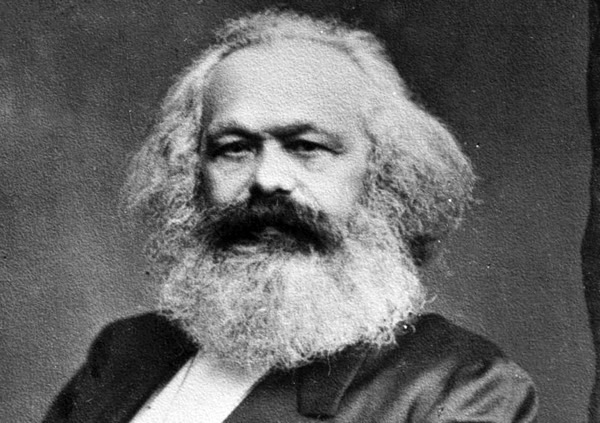

Wages are stagnant and inequality is rising, so maybe Karl Marx got it at least half right after all: capitalism, if left unbridled, carries the seeds of its own destruction.

We know the other half of Marxism is wrong: that after the working class rises up a utopian dictatorship of the proletariat will emerge. Three 70-year experiments tell us that all you get is a dictatorship – and repressive ones at that.

Developed economies now have an unprecedented set of economic circumstances. It is a bit like earlier new economic circumstances, such as the 1930s collapse and stagflation of the 1970s, when policy-makers did not know how to respond. The present baffling combination of wage stagnation, high profits and share prices, and low investment levels, inflation and interest rates was a result of several factors: social democratic parties adopting neo-liberal economics and thereby losing support; the collapse of organised labour; the erosion of the tax base; automation and disruptive technology.

This has meant that capital is able to take a greater portion of national income. So while there has been economic growth, the middle and lower end have not shared in it.

They are losing faith with the democracy that has delivered such a result and the danger is that they might lose faith with market capitalism that appears to be adding fuel to the flames of inequality.

Marx correctly pointed out, however, that capitalism needs consumers and would eventually collapse. It was a self-denying prophesy because capitalists realised that, and one way or the other allowed working people and people without capital who could not work a reasonable share of the pie so the system could continue. Until now, that is.

The Information Revolution is generating inequality equal to or greater than the Industrial Revolution but with few mechanisms to date to flatten out that inequality and the removal of mechanisms that once did so, such as the effective taxation of the fruits of capital; collective bargaining; and state intervention and provision of services.

All this is made worse in Australia by high immigration driving up property prices and debt. And it is about to be made worse worldwide by the economic cost of the collective failure to attack the climate crisis. Arguments that one nation can make no difference so why bother verge on the criminal.

I am not arguing for a return to confiscatory tax rates; destructive industry-wide strikes or state ownership of enterprise. Far from it.

But unless industry and government recognise that in the past 20 years or so, particularly in the past decade, labour’s share of the cake has shrunk so much that even as the whole cake gets bigger labour’s absolute amount remains stagnant.

It may allow governments and business to argue the economy is growing so we are all better off, but that assertion can only be met with disbelief by those on middle and lower incomes.

What is to be done? This week an Australian and Canadian economist published “Innovation + Equality: How to Create a Future that is More Star Trek than Terminator” (MIT Press). It makes some useful suggestions about the industrial world’s seemingly intractable economic woes. The Australian is Andrew Leigh, former ANU economics professor and now Labor Member for the ACT seat of Fenner, and the Canadian is Joshua Gans, an economics professor at the University of Toronto.

Their fundamental point is not to stop innovation, but rather encourage it and to have more of it. They argue that the Information Revolution and disruptive innovation need not necessarily result in increased inequality, even if, left without intervention, that is precisely what happens, as pointed out by the French economist Thomas Piketty.

But innovation destroys jobs – even simple innovations. The wheeled suitcase coming 4000 years after the invention of the wheel itself, the authors point out, destroyed the jobs of thousands of baggage handlers. Equally, innovation makes everyone else’s life better. So over all it is worthwhile.

Further, innovation is unpredictable. Who knows what will be invented or created or whether it will take off in a way to reward the inventor or creator. This means lots of people will be working on inventing or creating duds while a few lucky ones hit the jackpot. And that jackpot is getting ever bigger in the digital age.

The resulting greater inequality is in itself economically damaging.

To meet this, the authors argue for a greater safety net for those innovated out of a job and some reward for those who work to invent or create but do not hit the jackpot.

Education is critical. The book is about the US, but Australia has similar difficulties. Student debt is not as bad as in the US, but it remains an impediment to education. As the US, the teaching profession has been disgracefully down-graded. The pay should be raised so that it attracts the top 10 per cent of people going to university, and not be among the lower-ranked courses.

Of course, in Australia we waste money on optional extras for private schools that do not need it because they are already doing a good educational job. If that money went to deprived public schools instead we would get more education for our buck.

Education, the authors point out, is the most important mechanism to help people withstand the disruptions of the digital economy.CRISPIN HULL

On the innovation supply side, the authors argue that job licensing is a major impediment to innovation. Too many occupations have licensing requirements which have nothing to do safety and all to do with keeping new players out.

They argue for a simplified patent system where short-term patents are easy to get with more requirements for longer-term ones.

Hitherto, there has been a binary argument about the status of people in the gig economy, like Uber drivers. Are they employees, or are they contractors? The author recommend a new half-way point for such workers offering some of the benefits of full-time workers while keeping the contractor’s flexibility.

Essentially, the authors step away from the old left-right divide and argue for greater innovation leading to a bigger cake that is more evenly shared.

We simply have to overcome the “greed is good” mentality.

CRISPIN HULL

This article first appeared in The Canberra Times and other Australian media on 23 November 2019.