THIS week’s pledge by Foreign Minister Julie Bishop to counter-balance China’s power push in the Pacific with a greater Australian presence on the ground offers a sliver of hope in an otherwise grim international outlook. There has been much wringing of foreign-policy hands recently over threats to the rules-based international order. The sources of that threat can be distilled to three. Russia is unabashedly using an arsenal of weapons of mass deception. China is expanding its program of weapons of mass construction. And, meanwhile, the United States has slowly and unilaterally disarmed itself of great portions of its diplomatic power.

THIS week’s pledge by Foreign Minister Julie Bishop to counter-balance China’s power push in the Pacific with a greater Australian presence on the ground offers a sliver of hope in an otherwise grim international outlook. There has been much wringing of foreign-policy hands recently over threats to the rules-based international order. The sources of that threat can be distilled to three. Russia is unabashedly using an arsenal of weapons of mass deception. China is expanding its program of weapons of mass construction. And, meanwhile, the United States has slowly and unilaterally disarmed itself of great portions of its diplomatic power.

These are the three unexpected trends stemming from the end of Soviet communism and the fall of the Berlin Wall. At the time, we thought the peace dividend would fall in to our lap and there would be a virtual end to nation-to-nation military rivalry and conflict. Democracy and market capitalism had won, or so it seemed. But 30 years later, democracy, market capitalism, the rules-based international order, and a collective and multi-lateral approach to world trouble spots and trade are under threats unimagined when Soviet communism was defeated.

Russia has no shame. Even when caught out meddling in elections in democracies, it just denies it and carries on. It is using technology not in the imagination of the military mind a decade ago.

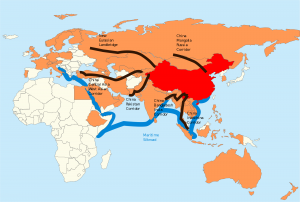

China uses construction power to widen its sphere of power and influence. It has built islands from reefs in the South China Sea and made territorial claims based on them, flouting international law and the rulings of international courts. It has offered easy loans to small nations, particularly on its Belt and Road Initiative, to enable Chinese trains, trucks and ships to go from one “friendly” access point to another across the Eurasian landmass.

Failure to repay, however, threatens the sovereignty of the small nations who are then compelled to cede leases over and equity in the access points in lieu of debt repayment.

The US appears powerless to do much about either China or Russia, perhaps in the case of latter because Russia has a hold over the President. The US’s heart might be in the right place – to promote peace and stability – but its responses to Russia, China and almost all other security threats have been the wrong ones. It has invariably preferred military to diplomatic solutions. And on the couple of occasions when the military option would have safeguarded human rights it sat on its hands for too long: Rwanda, Bosnia and Syria.

The Russian-Chinese-US foreign-policy combination has been quite unsettling for many in government, business and the wider public.

If we go on the way we are going, there will be a new world order based on what a nation can get away with rather than co-operative efforts to improve the lot of all nations and humankind.

It is worth looking at the aims of many nations’ foreign policies, compared to what those aims should be.

Most nations openly state that their national interest and their national security are the key aims. Overall, such an approach is bound to lead to conflict, suspicion and the defeat of those stated aims. It leads to over-reliance on military solutions and a selfish approach to trade that results in the loss of the benefits of more open trade.

The US has fallen into the trap for decades, fighting communism, drugs and terror. Its biggest mistake has been assuming its enemies’ enemies will always be friends rather than intermittent opportunists. The arms the US gave to local Muslim militias to fight the Soviets in Afghanistan in the 1980s, for example, were turned against the US in the 2000s.

Its winding back of diplomatic efforts in favour of military “solutions” were often illegal (invasions and drones). In the Middle East and the Horn of Africa they only gave rise to strong (and often armed) anti-US sentiment where none had been before.

Under President Trump the unilateral diplomatic disarmament in favour of military-strongarm tactics has been profound. Trump has surrounded himself with military people as advisers, staffers and in Cabinet and depleted the State Department of both numbers and corporate memory.

At the time Trump fired the man he appointed a year earlier as Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson (a man of no diplomatic or government experience), in March, there were 16 ambassadorial roles and nine assistant secretary positions without even nominations, including Egypt, Jordan and Qatar. A swathe of other senior and UN representative positions remained vacant. This was more than a year after the new administration took office. A large percentage of human-rights and development positions were unfilled then and remain so.

Trump seems pre-occupied with military rather than diplomatic solutions.

The glimmer of hope given by Bishop on a western fightback against Chinese influence in the Pacific was immediately over-shadowed by the US withdrawal from the UN Human Rights Council.

This brings us back to what should be the aim of foreign policy: the upholding of individual liberty and individual security using nation-to-nation and international co-operation.

There is no liberty without security and there is no security without liberty. They go hand-in-hand.

Engaging in proxy wars or siding with totalitarian strongmen to fight terrorism or drugs in breach of international law and human rights will never bring security. It will only bring escalation.

Turning away from co-operation to Put America First will not bring trade advantage. It will only bring a destructive trade war.

Turning away from international agreements as Trump has done with the Paris climate accords and the Iran agreement will not Make America Great Again. Nor will gutting the diplomatic infrastructure.

The military mindset is often tactical and transactional not strategic and relationship-building.

What will the US do in Iran without a multi-lateral denuclearisation agreement? Bomb the weapons sites every time Iran gets close to a nuclear weapon?

How will the US escape catastrophe from climate change without an international agreement?

Of the four centres of world economic and military power, only Europe seems to be holding up critical values.

The Russian and Chinese weapons of deception and construction have been unexpected and unexpectedly powerful.

To the extent that Europe is in trouble, at least the Brexit part of the trouble, can maybe be put down to Russian interference in the referendum. In the same way, Trump’s victory can maybe put down to Russia.

Nations and people on the side of personal liberty and the personal security that flows from it must push back.

To the extent that Australia and Foreign Minister Bishop do that it will be helpful, provided that it is not done as John Howard’s “Deputy Sheriff” but out of a genuine desire to help development in the Pacific.

If we do not help and we are also to be seen not to help with climate change and rising sea levels, they will turn to China for help. But with China the help will not come as neighbourliness, but in the form of a mortgage.

CRISPIN HULL

This column first appeared in The Canberra Times and other Fairfax Media on 23 June 2018.