wHERE’S the Money Coming From has been the classic political riposte against governments with big-spending promises.  In the past week or so, several well-placed non-politicians have been giving similar warnings.

In the past week or so, several well-placed non-politicians have been giving similar warnings.

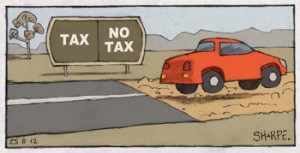

Australia’s tax system is simply not going to be up to the job of meeting the expectations people have of government, particularly in health and education.

Former Treasury secretary Ken Henry, present Treasury secretary Martin Parkinson and Richard Denniss of the Australia Institute have all argued for significant tax changes.

Their calls come as the Commonwealth and states slug it out over mining taxes. Treasurer Wayne Swan warned that any state that increased mining royalties would have its federal funding docked by an equivalent amount.

Swan rightly says that the federal mining resources rent tax was designed to replace state royalties, not be in addition to them. If the hypocritical Western Australian Government was so keen to get more money from the mining industry it should have supported the original federal proposal for a higher tax and waited for the inevitable trickle down to the states.

The mining tax was the only recommendation of Henry’s tax review to survive – and even it was watered down.

Henry said Australians should pay more attention to the need for higher taxes and less attention to self-interested business lobbies defending every perk. Without tax changes government finances would never return to the levels of before the Asian crisis.

Parkinson said that some of the big-spending items in the agenda of both major parties would require either deep cuts elsewhere or higher taxes.

Parkinson suggested that the tax cuts between 2000 and 2007 were too generous. The ballooning tax receipts at the time were partly as a result of a bubble rather than a sustained increase in economic productivity.

Denniss and his colleague David Richardson have crunched the numbers on tax concessions on superannuation. They conclude that they are costing more than the aged pension, so are self-defeating as an incentive for people to save for retirement so they do not draw the government pension.

In all, a bit of a mess. The genesis of it lay in the Howard years. The impression that the Howard Government was a lean, frugal, small-government Government is quite misguided. To the contrary, the Howard Government took the biggest slice of the Australian economy in history.

In 2005-2006 it took a record 26 per cent of GDP in tax receipts. In 2010-11 it was down to 20 per cent – so much for big-spending, big-government Labor governments.

This 20 per cent compares to a Howard Government average of 24 per cent during the seven years from 1999-2000 to 2006-07.

There is nothing wrong with that level of taxation. It is what you do with it that matters. Far too much of it was blown on middle-class and business welfare – particularly superannuation concessions and business tax benefits for investments that would have gone ahead anyway. Essentially, buying votes and donations.

That said, the Howard Government did two very sound things which have held Australia in good stead and point the way to a better fiscal future. The Howard Government ran surpluses and it introduced the GST.

The GST has been a salvation for government finances over the past decade and a bit. It has consistently delivered about 3 per cent of the GDP into government coffers come boom, bust, commodity price collapses, housing bubbles and bursts, Asian crises or even global financial crises.

Other taxes have proven more fickle. Capital-gains taxes retreat in a recession. People do not like to sell in depressed markets and those who are forced to sell get lower capital gains. State stamp duties plummet when the housing market falls in a recession. Fewer people can afford to buy. Few want to sell in a depressed market. Surviving transactions at lower prices yield exponentially less tax because the tax is imposed on a sliding scale.

Company taxes suffer because in a downturn profit is the first casualty. It falls disproportionately to turnover.

Meanwhile, expectations of government continue to grow.

The solution would be to increase the GST to 15 per cent and get rid of the exemptions, particularly on fresh food. Usually people on higher incomes spend a higher proportion of their food bill on fresh food.

Alas, that option has huge political difficulties. The original GST turned John Howard’s record 1996 majority into almost defeat at the following election when the Coalition got less than 50 per cent of the two-party preferred vote.

A scare campaign would be too easy.

There is, of course, another angle to Australia’s infrastructure needs and how to fund them.

Henry reminded his business audience that a 2010 Treasury Intergenerational Report said the population was expected to hit 35.9 million within four decades.

“We don’t have the infrastructure – that’s obvious – for another 14 million Australians,” he said. Australia doesn’t “even have the mechanisms for thinking about what sorts of infrastructure we’re going to need”.

“But the fundamental question, of course, confronting all of us about that infrastructure build requirement is how is it going to be funded,” he said.

But an even more fundamental question seems to me is why are government policies not directed a reducing that population increase so we do not have to have higher taxes and a poorer lifestyle?

Indeed having a more sensible population policy might be politically easier than increasing the GST.

At present, of course, those who benefit from higher population have the major political parties’ ears and provide the bulk of their money. They also have the money to provide the propaganda that hides the population elephant in the room.

Interestingly, Henry mentioned the importance of education. He said our system was not geared to cope with future pressures.

One defect in the education system seems obvious. It is not delivering enough voters with the wherewithal to see past glib political slogans and sensationalist media and take an interest in complex problems and the difficult solutions to them.

CRISPIN HULL

This article first appeared in The Canberra Times on 25 August 2012.