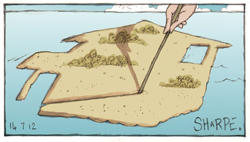

A CASE decided in the Family Court last week has revealed a quirk in Australia’s native title law and highlights once again some of the difficulties in native title.  One of the biggest objections to native title in Australia is that it ties up the land.

One of the biggest objections to native title in Australia is that it ties up the land.

The theory goes that Indigenous people cannot deal with their land. Native title vests in groups of people or trusts who hold it on their behalf.

It means the land cannot be mortgaged so it is difficult to use for housing or income-producing purposes.

Some suggest that native title over land holds many Indigenous people back because they have a place to go to and they go there, but they cannot use the land to get loans for business or housing, and they do not own so do not improve.

The countervailing view is that if Indigenous people could mortgage or sell their land it would not be very long before white fellas bought all the best land from them and they would be back where they were before the Mabo case in 1992 – dispossessed.

Last week’s case arose from a matrimonial dispute between a couple who resided on and off in the Torres Strait island of Mabuiag.

The de-facto wife was a native of the island and had lived in a house on the island which had been lived in by her family for several generations. The de-facto husband (who was not Indigenous) did a lot of improvements to the house. The couple had children together. Upon separation the husband ended up living in the house.

Justice Garry Watts of the Family Court had the difficult task of dividing their property. In a typical matrimonial case the house would be freehold, or in the ACT held on an automatically renewable 99-year lease (which amounts to the same thing). These things can be valued and added into the equation of matrimonial property.

The house on Mabuiag Island, however, was not held in freehold with a title deed registered in a land-titles office. Rather it was held under native title. The Federal Court decided in 2000 that the land on the island belonged to the Mabuiag people.

Now for some background. In the 1992 Mabo decision the High Court held that the land on Mer (or Murray) Island in the Torres Strait belonged to the Miriam people. It did so on the basis of common law. It was not a constitutional case. The court held that for centuries the common law of England, adopted by Australia, required English colonisers to respect the local ways of indigenous people.

To the extent that they had settled practices of land tenure, they were to be respected. However, the extent that the Crown and its authorities took the land for other purposes inconsistent with indigenous use, native title was extinguished.

That meant state governments could just take indigenous land – which they did. But after the 1975 Federal Racial Discrimination Act, they could not because it would be racially discriminatory.

Further, the Commonwealth itself could not just take indigenous land because the Constitution says the Commonwealth cannot acquire property except on just terms.

After the common-law decision, the Commonwealth codified native title under the Native Title Act using the powers it was granted by the 1967 referendum to make laws with respect to indigenous people.

In the Torres Strait it was fairly easy to prove a system of Indigenous land title.

Indeed, shortly after the Mabo decision I visited Mer and was asked to effect a transfer of title. I said that I could only document what was traditionally done because that was the nature of the title. So we walked around the land, noted the giant clam shells marking the border and the elders’ concurrence with the transfer and I wrote up an account of the transfer – perhaps the first documented transfer of native title in Australia.

The significant point is that, even in the Torres Strait, where houses, gardens and the like are held exclusively by individuals under traditional arrangements, the possession is not unfettered.

Justice Watts found that the wife’s house could not be rented out to anyone other than a Mabuiag islander. It could only be inherited by someone who intended to live on the island. Inheritance by someone other than the eldest would depend on the say-so of the eldest son. And in any event any transfer was dependent on the approval by the elders.

The Commonwealth’s legislative recognition of native title would almost certainly override any state land law about tenancies, inheritance and mortgages.

The upshot was that Justice Watts held the wife had a right to occupy the house under native title and ordered that the husband leave. But in assessing the value of the pool of matrimonial property the house was essentially worthless.

The case neatly illustrates the divided views about native title. On one hand it is worthless because it cannot be mortgaged or sold by individuals as part of their economic advancement. On the other hand, Indigenous people cannot lose their right of possession of native lands though purchase, mortgage, or, based on last week’s case, the operation of the Family Law Act.

One might well ask would the result have been the same if an Indigenous man had asserted his native title rights over a non-Indigenous wife in a family-law matter?

Incidentally, I do not begrudge the wife her house. Her case was very ably conducted by Cairns solicitor Sandra Sinclair on the law as it stands.

A further point about native title is the enormous amount of power held by elders, land councils and trustees. These people essentially determine who holds or uses the land.

The position in the Torres Strait is very different from the mainland. In the Torres Strait individuals can hold native title land exclusively and at least reap the crops and rent (if a tenant is approved). This is because traditional indigenous practice was to give individuals exclusive possession, and it is the traditional practice which the common law respects when recognizing native title.

On the mainland, individual exclusive use was never a part of traditional practice. Indeed, there is a good case that the High Court should never have extended native title to the mainland, as it did, on the basis of the Torres Strait case before it.

But it did, and we now have the conundrum of either dead land or no land for Indigenous people on the mainland.

But in the Torres Strait there would be a good argument for converting all native title to freehold.

In the meantime, as so much about Aboriginal affairs, the question of land tenure on the mainland remains almost insoluble.

CRISPIN HULL

This article first appeared in The Canberra Times on 12 July 2012.