WHOEVER wins on Monday, Kevin Rudd is right about the stranglehold of factional power. It happens because of funding, which is the root cause of Labor’s woes.  Labor relies for a great proportion of its funds on union dues. It means union-selected delegates get over-represented at the national conference and get too much say in policy development and who gets pre-selected.

Labor relies for a great proportion of its funds on union dues. It means union-selected delegates get over-represented at the national conference and get too much say in policy development and who gets pre-selected.

Union membership in Australia has declined dramatically in Australia over the past three decades. So has Labor Party membership and Labor’s primary vote.

But still the Labor caucus is now made up mainly former political staffers, union officials and lawyers.

Labor Party members get virtually no say in who should be their local member or have any policy input, so why bother. Declining membership, ironically, has caused even greater reliance on union funding.

It may take a bloodbath at the next election for Labor to realise it must ditch its reliance on union funding and union recruitment of MPs. It must broaden the power of members over policy and pre-selection and recruit members on that foundation.

Oddly, when Labor is at an electoral low it seems to attract members – as in 1975.

It may be that after an electoral bloodbath a Coalition Government will do what the NSW Coalition has done and legislate to cap or abolish union funds going to Labor or to advertising Labor causes.

Labor may protest against it, but ultimately it could be Labor’s salvation.

Remember, Rudd does not have a union background. That was fine when his government was going well, but at the slightest downturn the union heavies got him.

Julia Gillard has been a servant to the union movement and there is a fair argument that she went too far in winding back Work Choices.

In a way union power has been at the core of the Rudd-Gillard contest.

Labor has to change from a party whose funding is union-based because that results in its heart and soul being union-based. And if union membership is down to 18 per cent of the workforce, it is a pretty small heart and soul.

DOT DOT DOT

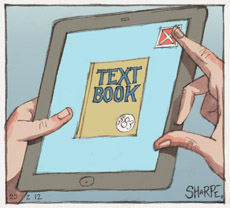

I FIRST entered the University Co-Op Bookshop 43 years ago. And not much has changed.

Prescribed textbooks still line the walls and are stacked on the floor. In the first week of semester you can hardly move.

A lot of still money changes hands, even though these days it via plastic card. Those academics lucky enough to have their textbook prescribed can still look forward to modest or even significant royalties.

It should change. And soon.

This week the Government received the Gonski report on schools funding. Money is short for education.

Well someone should look at the textbook industry and the government should use its market power to deliver more texts to more students vastly more cheaply. It can be done.

Some of my students have expressed despair at the $83 cost of the textbook for the introductory journalism course.

Spoiled academics, of course, have the power to prescribe or de-prescribe textbooks and to put books on reading lists or take them off. So publishers are quite willing to give them free books in the hope they make the lists. They get new editions and even multiple copies.

It is big business. About a third of Australian publishers’ $1.8 billion revenue comes from educational books. It can be done a lot more cheaply electronically, but not in the way the publishers would like.

The $83 text my students are complaining about comes in electronic form, but it costs an astonishing $53. This sort of paltry percentage mark down for the electronic version is typical. The publishers love it. For virtually no outlay or risk, the publisher is getting 60 per cent of the book price. And you can bet the author does not get an extra cut.

The paper version requires costs in paper, ink, transport, labour and retail rent and a large risk for unsold copies.

Now, every textbook sold in Australia was at some time, or still is, in an electronic form somewhere. And every new one will be.

For every student who cannot afford a paper textbook, this is a wasted opportunity. The vast wells of knowledge in paper books could be delivered much more efficiently and cheaply to students electronically. The electronic readers could be delivered through HECS loans.

A courageous Prime Minister could promise no student need live without a textbook by 2015. It would require some sort of imaginative public-private partnership with the publishing industry. Or if they did not co-operate, directly with authors, perhaps through the Copyright Agency Limited.

I am not arguing for a text free-for-all, far from it. Authors, editors and designers should get paid, the same or more than they get now.

It seems such a shame that so many students are denied access to so much knowledge which could be made available at so little cost.

The education sector should move rapidly away from paper texts. The lot could be done for a lot less than $1.8 billion a year and every student would have access to texts at a price that reflects costs reality — fraction of the cost of the paper versions, not at the exorbitant prices that publishers get away with because we have been acclimatised to paying so much for books.

Of course, you can lead students to a text but you can’t make them read, but my guess is that universal access would improve education.

Authors should like it. They would get more royalties because the secondhand market would largely dry up. Students sell texts for money and to make room. With encoded untransferable electronic books, which would be dirt cheap anyway, the secondhand market would wither.

There are other advantages to electronic books, especially in education. They can be annotated and the notes shared. They can be bookmarked and text-searched, thereby improving academic use.

It would be easier for students to bring all their books to campus. Many use public transport, making lugging paper versions quite a chore.

The inaccessible texts on computers in Australia are a wasted resource. There must be a fair and productive way to better use it.

CRISPIN HULL

This article first appeared in The Canberra Times on 25 February 2011.

@Kevin Rattigan: shop floor reps or careerist both (with a few exceptions) lack the experience and skill required to run a department as a minister –> very good ideas (usually generated collectively) but woeful ministerial implementation (see present government blunders) with the consequent waste of money

Re electronic books: the publishers are the de facto “choosers” of what book to publish based on its content and peer review. The electronic book tends to do away with the publisher and is in peril of generating “super blog” books with no pre-selection nor review process. So , in your view, who will decide wether the content is worthy and who will administer the distribution?

If the heart and soul of the Labor party is not the union movement then what is? Have we really achieved the workers’ paradise in Australia and employers are now the cowed victims of rapacious employees barely held at bay by legal constraints (Work Choices)? If so, and the “Neanderthal union bosses” finally disappear, from whence do the new members of the new “democratic” ALP come and how do they fund it? Involvement in party political activity appeals to few Australians anyway; those of a non-conservative bent surely join the Greens.

To me, the problem with the ALP is not that there are too many unionists (I don’t regard the careerist arts-law graduates, who spent a nominal 12 months in a union office before pre-selection, as “union heavyweights”) rather that there are not enough of the, old-style if you like, ex-shop-floor rep with a passion for social reform.