SPARE us another “free trade” deal with the United States. At APEC this week, leaders were agog with talk of windfalls gains all round and more jobs in Australia (or insert your favourite APEC nation as appropriate).  Prime Minister Julia Gillard was among the most effusive.

Prime Minister Julia Gillard was among the most effusive.

Now, freer trade does benefit all parties. Countries concentrate on what they are good at and export it and we all get more efficient and better off.

But that is not how free trade in America works. It is more a one-way street. Those goods and services which the US is good at must have free access into the other nations’ markets. But on the US side, up go quotas and the non-tariff barriers in the form of huge subsidies to US producers that make competition unequal if not impossible.

And all the time the US seeks ever stronger statutory protection for the services it is good at, particularly intellectual property: copyright, patents and trade marks.

The poorer APEC countries will have little hope of getting their agricultural products into the US fairly. Sugar is a good example.

In the US sugarcane growers get loans from the government based on how much sugar allocation they have under a quota system. After harvest if they can pay back the loan with some change, fine. If not, the government gets the sugar and the loan is expunged.

Now because a quota is imposed on local producers, surely a quota should be imposed on foreign producers. Isn’t that fair?

The US Department of Agriculture puts the subsidy at around $150 million a year, or about 15 per cent of the value of the crop – most of it to the half dozen big sugar producers.

How can a Latin American sugar grower compete with that?

Who is paying? American consumers, the ordinary voter, through higher sugar prices, and Latin American farmers who are denied access to the US markets.

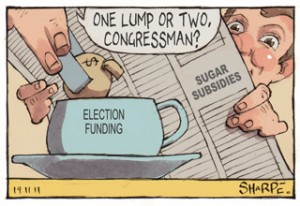

Why does Congress provide these subsidies (and not only for sugar) against the interests of the public? – Money.

Oddly enough, the way money works in US politics is easier to see than in Australian politics, because civic-minded bodies, like the Center for Responsive Politics, tell us.

It tells us that the sugar industry’s (and related public advocacy committees) top congressional beneficiaries in the 2008 election cycle (when a new Farm Bill was in the offing) were the chair of the Senate Agriculture Committee Chairman Tom Harkin who got $35,400; a Florida (sugar state) member of the House Agriculture Committee, Tim Mahoney who got $34,000 and the chair of that committee Collin Peterson who got $28,900. They are all Democrats, the party of the ordinary person, not big business.

Usually proposals approved by committees get legislated; those that don’t, don’t get legislated. So donations can be targeted to great effect — $100,000 for a $150 million a year subsidy sounds like good business to me.

Of course, the sugar industry and its action committees and lobbyists also provide information and arguments to congress members, and advertising to the public to support the “job-saving” schemes.

Is this bribery? Is this corruption? Is it criminal? No. No. No. There is no direct provable link between the campaign donations and the legislative outcome. This stuff is not done with brown paper bags. And industry influence is as much to make sure nothing is changed rather than that something is changed. So any link is harder to prove.

(For more on this I commend Lawrence Lessig’s “Republic, Lost”, out last month.)

Sugar is a particularly egregious example, though important to Latin American APEC countries and Australia. Similar things happen in other industries. And with Congress’s loose party discipline, industries can pick off critical Congress members to ensure their positions are looked after — and too bad for the general public.

While ever the US political system runs this way (as it has since around the mid-1990s) we should forget “free trade” deals. If they are worth having, they won’t get through Congress. If they get through Congress, they are not worth having.

DOT DOT DOT

ON THE intellectual property front, the US has engaged in a perpetual campaign to ever widen copyright and patent protection through domestic law and international agreements.

Laws to give extra copyright and patent protections seem to whizz through Congress – almost one every two years – while any proposal that burdens business, particularly environment or tax, languishes.

In the last free-trade agreement with Australia, Australia succumbed to US demands to increase copyright protection from 50 to 70 years. The US has led the charge to put criminal provisions into copyright law to protect what is essentially a private interest.

The US promotes tricks to extend the normal 20-year patent protection for medicines by permitting extended time for new forms of the same medicine.

Of course, when the boot is on the other foot and another country has subsidies, even those in the broad public interest, the US riles against them and tries to have them abolished in the name of “free trade” – Australia’s Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme is a case in point.

Unlike the US sugar scheme, the PBS is in the broad public interest. It has generated a large Australian industry producing low-cost out-of-patent medicines, making medicines more affordable.

US business has managed to corral public law-enforcement enthusiasm to enforce copyright breaches which environmental and occupational-health-and-safety enforcers can only dream about.

The US even sought an obtained extradition of an Australian, Hew Griffiths, in 2007 for breaches of copyright. Griffiths had never been to the US before. He got four years’ jail. Sure, it was a fanatical breach of copyright in software, but not for any financial gain – just allowing fee copying. But fancy those big software companies first getting the criminal provisions inserted and then being able to marshal public resources to enforce what is essential a private right to make an example of someone. The public gets virtually nothing back from the resources it puts into software copyright. After 70 years the software will be valueless to the public, unlike, say, a Dickens novel, or a medicine after the 20-year patent ran out.

And some public return should be the quid pro quo for the state giving the monopoly in the first palce.

Software should have got a seven year monopoly and then been public, but that would never happen given the political power of Microsoft and others through their congressional donations (a strategically placed $3 million per election cycle from Microsoft alone).

And speaking congressional dysfunction and this week’s visit by President Obama, Congress is quick to authorise spending for military expansion – now into Darwin – but paralysed when it comes to raising tax to pay for it.

If the US was really concerned about peace and security it would not be wasting ever more money on war, foreign bases and military build-up, but use the money to repay its prodigious foreign debt. That poses a greater threat to US supremacy over China than any military posture. But Congress seems blind to it.

CRISPIN HULL

This article first appeared in The Canberra Times on 19 November 2011.