“Not though the soldier knew

“Not though the soldier knew

Someone had blundered.

Into the Valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.”

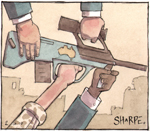

MAYBE some good will come out of the charging this week of an Australian soldier with manslaughter over a botched raid in Afghanistan.

It might cause some people to reflect that the whole operation in Afghanistan was a botched raid as was the operation in Iraq, and that perhaps a far wider net should be cast over who is to blame and who have committed criminal acts.

The promised parliamentary debate on Afghanistan is all very well, but it will only serve up platitudes and assertions. What we need in Australia is an inquiry into how and why we got into these wars; how much they will cost; and how and when will we get out.

Now we have got a Parliament that is more than the Executive’s rubber stamp this might be possible. Hitherto both major parties have been happy to cover up or at best remain silent over each other’s misdeeds.

Inquiries into matters of far less moment have been conducted in Australia. These wars satisfy the usual reasons that people seek an inquiry: the public was misled; large amounts of money have been spent or misspent; lessons should be learned so we don’t make the same mistakes again; and people have been killed and lives wrecked.

Inquiries elsewhere have not and will not tell us why our leaders acted in the way they did. But inquiries in Britain and the Netherlands show the value of the exercise.

In the US, the position has been much as it has been in Australia – virtually no inquiry or oversight by the legislature or anyone independent with coercive powers. There, as here, neither side of politics is willing to expose the folly of war.

The conflicting reasons for going to war alone require an inquiry. The Australian public has been variously told we engaged in the wars to reduce terrorism; to reduce the chance of a regime or terrorists using weapons of mass destruction against us; to change evil regimes; to support democracy; to stop abuses of human rights; and to support the US alliance.

Only the last has been consistent.

If that is the major reason for Australia going to war in places which would otherwise have no real bearing on us, we should examine why the US went to war or if our leaders questioned those reasons.

As well as the reasons for war mentioned above we can add the following to US motives: to secure the supply of oil; revenge for the 9/11 attacks; and to finish the job begun in the first Gulf war.

For the past 65 years the US’s foreign policy has suffered from the Munich syndrome punctuated only too briefly by the Vietnam syndrome.

The US came away from World War II with huge self-confidence about its capacity to use force to defeat tyranny elsewhere in the world. For decades it “stood up against communism” often mistaking nationalist movements for “communist” ones. In the name of not appeasing tyrants as British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain did in with the Munich agreement with Hitler in 1938, the US meddled in other country’s affairs, overturning or attempting to overturn governments in Iran, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Cuba, Chile, Panama and countries in Africa and the Middle East.

After the Wall came down it soon resumed the role as the world’s policeman replacing “communism” with “terror” or “Islam jihadism”.

No more Munichs, the policy-makers argued, even though the comparisons between tinpot communist regimes with Hitler’s powerful Germany were very long bows indeed.

Yes, there have been occasions when people in some of the affected countries have rejoiced at the regime change, but the gratitude never lasts long, particularly if US troops remain in occupation.

Australia, has too often been deputy policeman.

Too often the US intervention and our part in it has resulted in both countries being less, not more, secure.

Any inquiry into these wars should question the working of our alliance with the US. Australia has blindly followed the US into every major war since 1945. Other allies have not. Many rightly baulked at Vietnam and Iraq.

The costs of the wars have been horrendous. Aside from 4420 American and 316 other Coalition of the Willing dead soliders, the Iraq war has cost the United States $US900 billion in direct budgeted costs alone. Economist Joseph Stiglitz estimates it will go beyond $3000 billion when you look at veterans’ care and flow-on economic cost caused by US deficits. Leave aside, the Iraqi dead, injured and displaced.

The Afghan war has cost the United States $US300 billion in direct budgeted costs alone. It will eventually treble that even if fighting stopped tomorrow.

Australia is spending $1.2 billion a year in Afghanistan and we have lost 21 soldiers.

For what? Do the military and political leaders still imagine they can install democracy in a backward country of warring tribes? Or do they still imagine that even if they somehow created a democracy that it would stop terrorist attacks. After all, many major recent terrorist attacks were planned and executed in democracies often by citizens of those democracies.

The Chilcot inquiry in Britain has finished its public hearings and will report later this year or early next. It has heard 140 witnesses including former Prime Minister Tony Blair and several ministers.

The evidence has been fairly damning of Blair. He still persists with the manifest hyperbole that Islamic jihadism is the greatest threat to security in the world today. Forget hunger, poverty, disease, climate change, oil running out or water crises. But the inquiry has been exposing his mendacity over Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction and exaggeration over Iraq’s threat to British security.

The Australian public deserves some accountability from the leaders who took us to war. It is not enough to hold only the soldiers on the ground accountable for their actions. There is a fine line between a medal and a manslaughter charge. And the actions of a soldier under fire have more moral ambiguity about them than the calculated actions of political leaders who drag a whole nation into war on spurious and shifting grounds.

Alfred Tennyson writing about the folly of the equally mad Crimean War in the mid-19th century said that it was not for the soldier to reason why, his was but to do or die. Well it is for the public to reason why, and to wonder whether the right people are on trial here.

CRISPIN HULL

This article first appeared in The Canberra Times on 1 October 2010