MY FIRST national tallyroom experience was at the 1969 election. As the poverty-stricken son of a clergyman I was chosen with a few others from the Political Science I class by Professor Fin Crisp in response to a request for casual labour for election night.

MY FIRST national tallyroom experience was at the 1969 election. As the poverty-stricken son of a clergyman I was chosen with a few others from the Political Science I class by Professor Fin Crisp in response to a request for casual labour for election night.

I think the show was then being run by the Department of the Interior. I was going to be putting the numbers up on the board as they were phoned in from polling booths.

Very excitedly, I rang my parents in Beechworth, Victoria, to tell them their just-turned-18-year-old son was to be on national television.

However, my father thought television was the work of the devil and refused to have a set in the house. Expense might have had something to do with it, too.

Television had only come to Beechworth in 1966, 10 years after its introduction into Australia. Technology travelled slowly then.

For some months after television’s arrival in Beechworth, people parked their cars each evening outside Garland’s Electrical Store so they could see the silent TV in the shop window. Other people brought chairs and rugs and sat on the footpath drinking coffee from thermoses and beer from bottles in brown paper bags.

They even stood up for God Save the Queen at the end of the evening’s broadcast around 10.30pm.

Others visited those lucky or wealthy enough to have their own sets. My father had watched the 1966 election results at a parishioner’s house. He had seen the young students posting the numbers on the tally board in front of the TV cameras.

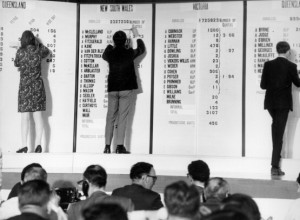

I have even found the accompanying photograph of the 1966 tallyroom taken by The Canberra Times’s Peter Ford. (You can see this by visiting the website.) I think that is the ABC’s James Dibble in the foreground. And that lad on the right is wearing desert boots. How late 1960s can you get?

Anyway, my father relented, and in October 1969 the first television set was installed in the Rectory, Beechworth.

My father was at least partly right when he said television was the work of the devil. It slowly corroded Beechworth’s social life. The Tuesday night cinema went. Attendance at Lions, Rotary and other services clubs fell. Table tennis, card nights and other evening social and sport competitions withered. Even the plays put on by patients at the mental hospital and prisoners at the jail could not compete with the insidious magnet of the cathode ray tube.

On the evening of Saturday 25 October, 1969, the magnet had drawn my parents in, too. They were set to watch their son on national television. They had even invited selected parishioners to the proud spectacle.

Imagine, therefore, my horror upon arrival that afternoon for the practice session at the tallyroom when an electoral functionary told us of great improvements for the public viewing of the seat-by-seat voting numbers.

Instead of walking on a platform in front of the tally board (as pictured in 1966), we would stay on a platform BEHIND the tally board. It was a mirror of what was in front. Below the name of each seat a board the size of a computer screen hinged at the centre could be swivelled around and the new numbers put up from behind before the board was turned 180 degrees to face the public.

Alas, the most of me that appeared on national television that night was my hands as I swivelled the boards around.

Late in the evening I tried a facial cheerio through a half-open board, but, as I later found out, my parents still didn’t see me.

At least in those days television had a single channel and for the next couple of decades only a few channels so that people had a talking point the next day: “Did you see X last night?” There was still some community about the medium.

Everyone, of course, was glued to the TV on election night, unless you were lucky enough to be at the tallyroom.

The tallyroom was electrifying in 1969 (the night of Don’s Party) and even more so in 1972. Gough Whitlam declared victory in the tallyroom. Television cross-overs and outside broadcasts were more difficult then. It suited the media to have a central place to see the counting. And given the media were there, the politicians followed. They were there to share the glory or disappointment. A bit like a football grand final.

Media, and the technology it used, defined the event.

The last leader of a major party to visit the tallyroom was Bob Hawke in 1983. He dramatically entered the room in the late evening with his wife Hazel to declare victory amid a jostle of microphones and cameras.

In the early 1990s, direct computer feeds of results to media organisations on the floor of the tallyroom made the big board little more than a superfluous prop. But the TV stations still liked it even if the gurus with screens and graphics programs on their makeshift tallyroom-floor studios were ahead of the board.

Also, the public continued to have access to the tallyroom, subject to seating and standing space. So it has remained an event.

In the past couple of elections, though, the internet has allowed the count to be delivered to every home in the nation, making the big board an anachronism. The people posting numbers were well behind the internet.

After the 2004 election, the Australian Electoral Commission proposed abolishing the tallyroom on the grounds of cost, but the media protested. They like the event.

But just as the media and technology have changed, so have the politicians. They now like every event choreographied and the tallyroom is no place for the set piece. Also, the public these days is less civil and more unpredictable so politicians like to avoid contact with the great unwashed. So they stay safely with the party faithful at venues where the public cannot enter. The tallyroom is no longer a magnet.

Nonetheless I shall be at the tallyroom tonight with half a dozen journalism students from the University of Canberra. We will be posting to www.NowUC.com.au, the School of Journalism’s online publication.

The journalism students will be tested, and so will the tallyroom itself. If few or no candidates turn up and the public and pressure groups are not interested, the tallyroom will have little to offer.

Once again technological advance will force us to trade some social fabric for more information more quickly — and a great sense of national occasion in national capital will slide into history.

CRISPIN HULL

This article first appeared in The Canberra Times on 21 August 2010.