LIKE democracy, freedom of speech has a paradox. Democracy’s paradox is obvious: what if they vote for dictatorship?  The paradox of freedom of speech is similar, but less obvious. What if someone, in the exercise of their freedom of speech, buys such a large portion of the means of publication that they drown out the freedom of speech of others?

The paradox of freedom of speech is similar, but less obvious. What if someone, in the exercise of their freedom of speech, buys such a large portion of the means of publication that they drown out the freedom of speech of others?

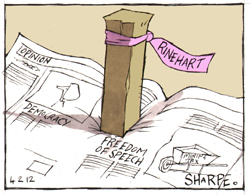

Gina Rinehart’s purchase this week of enough shares in Fairfax to make her the largest single shareholder highlights that paradox

It comes at a time of several government-instigated inquiries into the media which in effect boil down to addressing this very paradox. At what point does an individual’s or corporation’s acquisition of the means of freedom of speech, itself become an unacceptable denial of other people’s freedom of speech?

In what circumstances should government prevent people from controlling more of the means of freedom of speech, even if that means some curtailment of those people’s freedoms?

At some point, of course, the two paradoxes intersect, exposing the vulnerability of both democracy and freedom of speech. There comes a time when a few people have so much control over the means of communication that their message dominates public discourse. And it dominates it to such an extent that the broad mass of voters cannot be properly informed and cannot make an informed vote.

The paradox of democracy is resolved once you have an informed electorate: an informed electorate would simply never vote for a dictatorship.

An informed electorate, moreover, would insist that the means of communication are kept multiple and diverse so the electorate can remain informed.

This is why our High Court has held that free political communication is essential to the working of our constitutional democracy.

This hypothetical – dictatorships and suppression of free speech – is the extreme point, but it nonetheless illustrates the danger. There is a large grey area before you get to the extreme.

Some large interests have significant control of a big bit of the media and can distort some of the debate about some of the issues, resulting in government policy which favours them, rather than the broad public interest.

Australia is perhaps at the light grey end of this grey area. Seventy per cent of our print media is owned by Murdoch who pushes a definite political agenda. And big money can engage in television advertising campaigns at a relatively low cost to them. These distort the debate, frighten elected representatives and ultimately influence policy against the public interest. We have seen this with the mining tax and poker machines, for example.

Of course, lots of free speech continues – journalists and the public write and talk about lots of other issues and present other views. But it is not a fair match for a relentless well-moneyed campaign or a determined media owner.

So will Rinehart’s investment in Fairfax have much effect? Incidentally, it may not be a very astute investment. Fairfax shares have been steadily falling as it – like newspaper companies throughout the developed world – tries to get a successful business model in the internet age.

That being the case, we can only assume that Rinehart wants the shares because Fairfax’s media outlets influence public opinion and politicians’ response to it.

Whether she wants that to further her mining interests or to further her personal political ideas, or both, is hard to tell.

But being the largest shareholder in Fairfax is no guarantee of having significant influence on editorial policy.

At least on a hypothetical level, shareholders in a public company do not have a say in the running of the company – ownership and management are separate. Even if a large shareholder gets a seat on the board of directors, the board cannot dictate editorial policy, though it may have a hand in the hiring and firing of senior executives, but usually only the CEO, not the editors of individual publications.

On a human level, however, the occasional word and trickle down influence can have an effect.

But this is nothing like the active executive role that Rupert Murdoch has taken with his media outlets — either taking executive positions himself or directly hiring and firing other executives including editors.

The public should always be vigilant that this does not happen to Fairfax. Certainly we can expect the institutional shareholders, the directors they appoint, and the independent directors are not going to let that happen. They realise that the commercial success of Fairfax depends on editorial policies being seen by readers as independent.

That is not the case with The Australian. It is not a commercial success. It is cross-subsidised by other Murdoch holdings. It is a vehicle for Murdoch’s political influence. As a commercial enterprise it would have closed long ago.

At Fairfax the portion of revenue and profit coming from newspapers has fallen over the past decade, but the papers are probably still quite profitable.

The profitability of Fairfax’s Australian Financial Review would be threatened by any perception that its editorial policy towards the mining industry was influenced by the personal view of a Fairfax shareholder.

Rinehart’s place on the Fairfax board is of far less moment for free and diverse political speech in Australia than Fairfax’s capacity to meet the internet challenge.

Like most newspaper companies, it still has a silo mentality — one paper with its own editor for each geographic area and one for its business paper.

It should put the whole lot together on one internet subscription. Readers would select their geographic or business and the application would organise the content accordingly. But all Fairfax material would be there, as would the foreign services it selects and delivers (with an Australian eye).

As the price of ipads and the like plummet and the cost of paper distribution goes up, newspapers will only be delivered on ipads and the like. They may be like mobile phones – come free with your two-year subscription to the service.

The Sydney Morning Herald’s subscription and app for ipad is little short of miraculous. But it is only one paper, not all Fairfax content. To challenge the “print” or text dominance of Murdoch, Fairfax should have a long-term aim of a single national subscription with regional and specialty sub-programming – in effect having “newspapers” in every state and territory and a national newspaper.

I would much rather Fairfax be doing it than allowing the present technological hiatus to allow some telcom or other big corporation with no journalism heritage to grab the market share.

CRISPIN HULL

This article first appeared in The Canberra Times on 4 February 2012.

G,day Crispin,

You make some very convincing arguments with regards to not only the concentration of media ownership in Australia but also the future of traditonal media outlets in the digital age. Murdoch is somewhat already putting all his papers under the ‘news.com.au’ banner and I agree that Fairfax could do a better job doing the same as you have outlined above. I would have no qualms paying for a single subscription if I could purchase specific sections of different Fairfax publications including regional content. I am currently writing about these topics for my masters and I will link to your article accordingly. Cheers, Dean Casey