IT WAS a violent attack with a Swiss Army knife. It was contrary to major cultural and moral precepts of my upbringing which I have kept for nearly all my adult life.  Nonetheless, I did it.

Nonetheless, I did it.

For decades I was taught, believed and practiced the precept that books are sacred: to be bought and not sold; to be opened and closed in a way that protected spines; to be lent only one at a time and to chase up returns; to be ordered on bookcases in way that enables quick retrieval of critical information; not to be thrown out or burnt – a sort of Ten Commandments of Books.

Yet, here was I, kilometres from civilisation in the Clyde River wilderness and I did it. One of my bushwalking companions had put down his half-read book – a book of Stephen Jay Gould’s essays – and I had left my books behind and had nothing to read.

I picked it up and started to read. But he would be back soon, so there was only one thing to do if I was to have anything to read in the next day or so.

I snapped back the spine – breaking Commandment Two. Max Bourke, my Year 8 English teacher had taught our class how to open books carefully at each end and fold the pages back so the spine did not snap. These days, however, better glue makes it less of a problem.

Then I opened the scissors of the Swiss Army knife and cut the book in two.

My busk-walking companion, who had had a similar book-revering upbringing to me, returned. He was outraged. No, he was not so much outraged as morally affronted. This was an act of grave, criminal vandalism – utterly unforgivable.

“It’s, okay, Patrick,” I said, rather sheepishly. “Of course, I’ll buy you a new copy when we get back to Canberra.”

He replied: “That’s not the point. It was a BOOK.”

That was more than a decade ago.

Sometime after that I moved house and had to downsize dramatically. Sacrilege: I sold more than 3000 books, breaking the first commandment. I kept a few hundred, but barely opened any of them in the next six years, relying instead on the internet and new books.

The paperless library is upon us, as is the much-derided paperless office.

In the past week I have had to help move my wife’s law library and also find a couple of five- or six-year old extremely important building and planning documents out of thousands of pages of roughly filed documents. It took ages with mixed success. And I might now have to pay for a new survey.

In the past year, on the other hand, I have taken to scanning everything important and chucking the paper out. With good folder and file names stuff is so easy to find and you don’t need filing cabinets.

You can also copy and paste the filenames of invoices into a spreadsheet so you can add up spending and income for tax returns and the like.

I recall that when computers were first introduced into offices – and newspaper offices were among the first – we all insisted on making printouts for fear of losing material. These days, I want material scanned into the computer so I know it won’t be lost or accidentally thrown out.

When The Canberra Times moved to Fyshwick in 1987 journalists were incredulous when told there would be no printout machine. The first time stories would hit paper would be when the newspaper printed. But if there’s no paper, there’s no story, they thought.

Now the National Library is scanning every newspaper from its first edition.

The law-library move was instructive. Just the two main law reports – the Commonwealth reports since 1903 and NSW reports since the middle of the 19th century – make about 400 volumes. At the present one-off rate of $150 for back volumes that is $60,000 worth, and several thousand dollars a year to keep them up to date.

How much easier and cheaper is it to buy an annual internet subscription to those plus seven or eight more services (updated as the judgments, legislation and regulations change). The internet subscription is easier to search and easier to upload on to an ipad to take into court.

Sure, the leather bound volumes look impressive, but at what cost? Moreover, they occupy several square metres of office space at $400 a square metre a year. And they weigh nearly a tonne. The whole lot would fit four times over in my 3kg laptop.

My guess is that the official law reports will not be available in paper within a decade.

The libraries of other professions will go or have gone the same way.

One of the big questions in this is copyright, or rather ensuring a fair return to authors for intellectual effort.

In theory, though, there should be more money available for authors in an electronic world. The bulk of the cost of delivering the words and pictures in book form is the paper, ink, distribution and the costs of retail outlets. The costs of setting up permanent electronic access to a work (in an uncopyable form) are minimal compared to the cost of selling paper copies.

Once readers see the advantages of not having to store and move the books and having access to them wherever they take their electronic book reader as well as the capacity to search the text and increase its type size, they should pay as much for the electronic book as the paper one giving ample return to authors.

If I could snap my fingers now and have the remaining couple of hundred books in my library be converted to electronic form, I would happily burn them — a breach of Commandment Five.

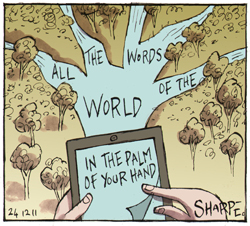

After all, it is not the paper, cloth and leather that matter, but the readable words. The point is not that it is a BOOK, but that it is something to read. Electronically, you can take a thousand books on your travels. We are fortunate in the 21st century that we can take a library with us anywhere. Even into the Clyde River wilderness.

CRISPIN HULL

This article first appeared in The Canberra Times on 24 December 2011.