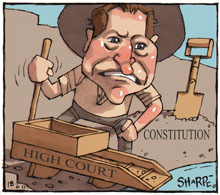

SO OFTEN when some injustice or unfairness arises, the aggrieved parties imagine the High Court and the Constitution will step in to save them. Most recently it was by Andrew “Twiggy” Forrest the head of the mining company Fortescue Metals.

SO OFTEN when some injustice or unfairness arises, the aggrieved parties imagine the High Court and the Constitution will step in to save them. Most recently it was by Andrew “Twiggy” Forrest the head of the mining company Fortescue Metals.

He has got it into his head that because the Government’s mining tax will be more favourable to multi-national companies than struggling Australian operations like his that it must be unconstitutional. Upon the release of the draft legislation last week he threatened a High Court challenge.

He shares a fairly common misapprehension that the Australian Constitution contains rights and protections against governments over-stepping the mark.

They have been watching too many American movies.

In fact the Australian Constitution provides precious few freedoms, rights and protections – certainly nothing a vigorous as the US Bill of Rights.

The two Constitutions have a lot of similarities on the structure of government, but on human rights they are entirely different because they arose in different circumstances: one was a nation emerging from a successful a rebellion against the British Crown; the other was a nation timidly retaining strong links to the British Crown.

The pedigree of the US Constitution included Tom Paine’s Rights of Man and a general belief in individual freedom and worth. It abhorred the English class system and the monarchy.

More importantly, the Founding Fathers in the US had a suspicion of government – especially autocratic or monarchical government – and saw the need to restrict it. On the other hand, the Australian Founding Fathers regarded themselves as part of the British Empire, not rebelling from it. In Britain, Parliament was sovereign and could pass whatever laws it liked.

The US Bill of Rights is a list of places the Congress cannot go and rights for individuals: speech, religion, assembly, silence (“taking the Fifth”), due process, trial by jury, property and so on. The Supreme Court has interpreted them liberally.

The limits placed upon the Commonwealth Parliament by the Australian Constitution, on the other hand, are mainly in the division of powers between it and the states.

There are only a few other limits and they are generally not described as individual rights. Interstate trade must remain free; a religion cannot be established no religious tests imposed for Commonwealth office; the right to trial by jury is limited to “indictable offences” and can be circumvented; the representative system implies some limited rights to vote and does not permit laws that impose unreasonable restrictions on the freedom of political communication; and the Commonwealth cannot acquire your property away without compensation. And that’s about it.

Forrest imagines that the Government’s proposed mining tax is unconstitutional because the burden lies almost totally with Australian companies and multinationals will get away without paying. So Australians are being denied their property rights.

He is correct in saying it falls more heavily on Australian miners because the law allows deductions against the tax, which is fine if you have a big balance sheet against which to deduct (as most multinationals have) but useless if you are a start-up explorer as most of the Australian miners are.

He also says it is unfair (and therefore unconstitutional) because the whole burden will lie with Western Australians and Queenslanders and the other states will pay nothing.

But, alas for Forrest, the Australian Constitution has got nothing to do with fairness.

Forrest said, “As it stands now, any Australian who has a tax which allows multinationals to pay less per-dollar-profit than what they do, that should be challenged. That is totally against the Constitution.”

Well, sorry Twiggy, no it’s not. Nor is the argument he reportedly put in a letter to Prime Minister Julia Gillard about Western Australia and Queensland.

What does the Constitution actually say about these things?

It says, “The Commonwealth Parliament has power to make laws with respect to . . . taxation; but so as not to discriminate between States or parts of States.” And it can make laws for “the acquisition of property on just terms from any State or person”.

If Parliament passed a law imposing “the Andrew Forrest impost” of $1 million on Andrew Forrest, that would not be a tax, but an acquisition of property. For an impost to be a tax it must apply generally to events of a kind.

An income tax of 80 per cent on all incomes over $500 million would be a tax, not an acquisition of property. The fact that, say, as it happens, the only people in Australia with incomes above $500 million live in Western Australia does not mean the tax discriminates between the states. To discriminate, the tax must impose a burden related to the person’s “Western Australianness”.

If you tax all miners, but mining only happens in Western Australia, it does not discriminate, because someone could open a mine in NSW and would incur the tax.

If , however, you imposed a tax on “all Western Australian miners” it would discriminate, because if someone opened a mine in NSW they would not be taxed.

The tax certainly does not discriminate against a state merely because a greater proportion of the transactions being taxed happen in one or two states. On that basis, the GST would discriminate against NSW.

Forrest’s other point — that the tax falls more heavily upon Australian miners than multi-nationals — is irrelevant for constitutional purposes.

The fact the tax is imposed on activity (mining profits with no possibility of deductions) which affect only a few people or corporations (320 Australian miners) does not make it an unjust acquisition of property, provided the tax is structured in such a way that anyone who engages in that activity cops the tax.

If the law said these listed miners and no others will be taxed, it would be an unjust acquisition and unconstitutional. But this law does not do that.

Big Tobacco should also take note. The Commonwealth’s proposal to deny them the right to put their trademarks on their cigarette packages is not an unconstitutional acquisition of property for the simple reason that the Commonwealth is not acquiring any property. It is not as if the Commonwealth is going to go into the business of selling Marlborough cigarettes having “acquired” Big Tobacco’s trademark.

As it happens, I don’t think Forrest or Big Tobacco have much of a case, either legally or morally.

Nonetheless, the Constitution should to protect people from unfairness or injustice and guarantee basic rights, which it does not do now. It was not designed to. Under the 1890s design, Parliament was given that task and on many occasions it has failed.

CRISPIN HULL

This article first appeared in The Canberra Times on 18 June 2011.